A key atmospheric indicator in the Pacific Ocean region has just surpassed the accepted threshold for El Niño, increasing the likelihood of abnormally dry and warm weather in Australia later this year.

There has been a lot of talk recently about the potential for a strong El Niño in 2023. Most of this climate driver discourse has been centred around rapid and widespread warming in the tropical Pacific Ocean during the last few weeks, and the anticipated persistence of this warming in the months ahead.

However, ocean temperature is only one part of the puzzle when it comes to El Niño. The atmosphere above the Pacific Ocean needs to respond to the oceanic warming before a fully-fledged El Niño can be declared.

When is El Niño underway?

The Bureau of Meteorology uses both observations and forecasts from several oceanic and atmospheric indicators to monitor whether El Niño, La Niña or neutral conditions are present in the Pacific Ocean.

For El Niño to be declared, any three of the following four criteria need to be satisfied:

- Sea surface temperature: Temperatures in the NINO3 or NINO3.4 regions of the Pacific Ocean are 0.8 °C warmer than average.

- Winds: Trade winds have been weaker than average in the western or central equatorial Pacific Ocean during any three of the last four months.

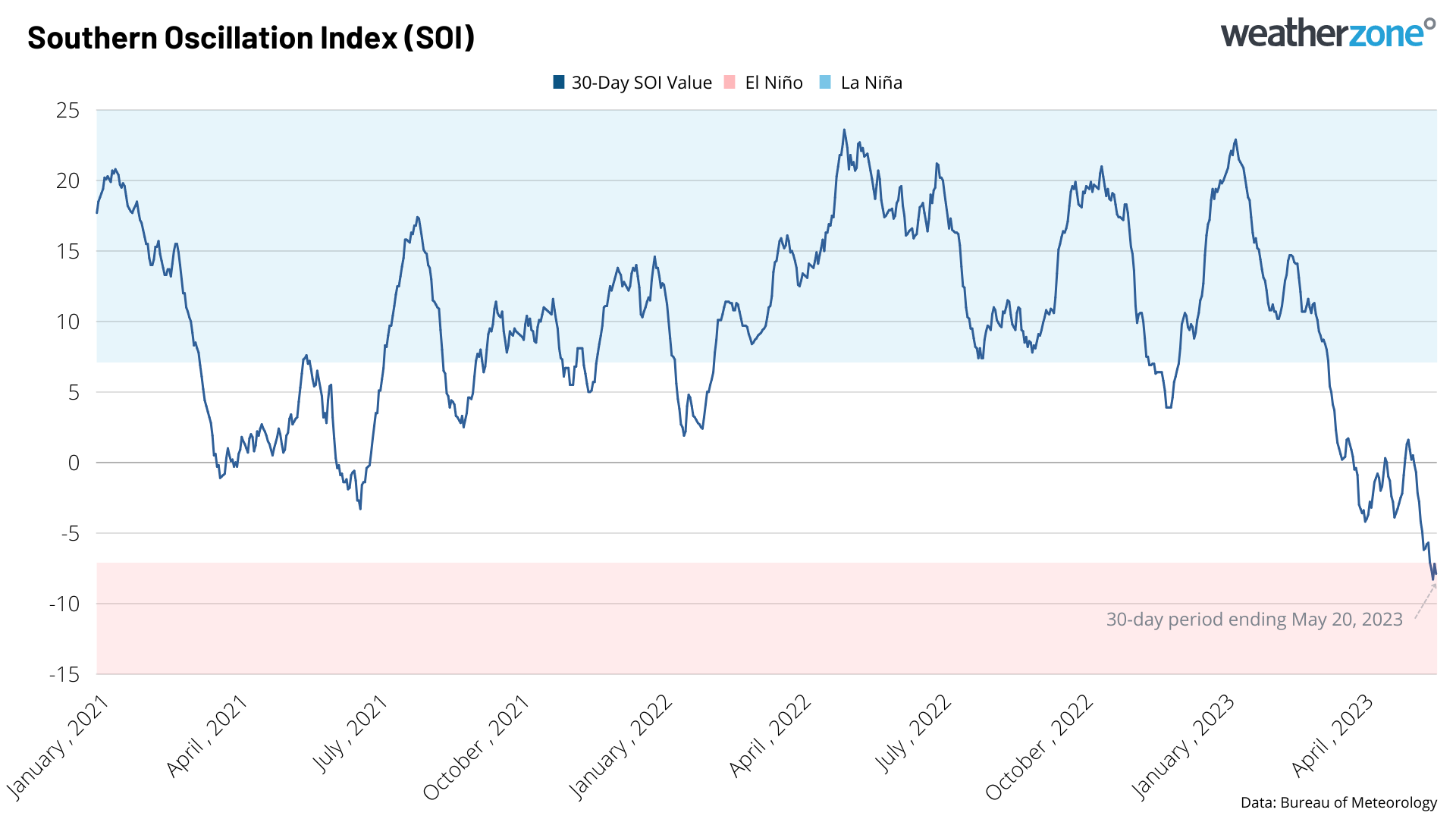

- Southern Oscillation Index (SOI): The three-month average SOI is –7 or lower.

- Models: A majority of surveyed climate models show sustained warming to at least 0.8 °C above average in the NINO3 or NINO3.4 regions of the Pacific until the end of the year.

Two out of four

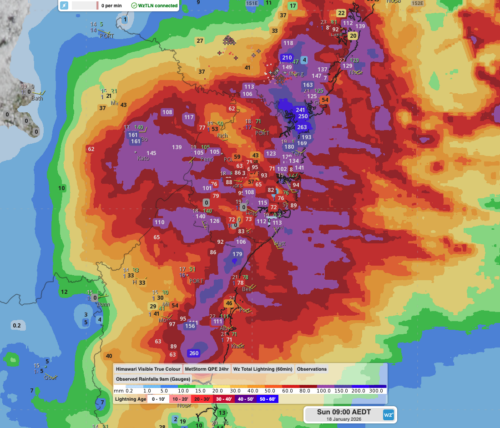

At the start of last week, criteria one and four from the list above had been met. The sea surface temperature in the NINO3 region was 1.12º above average (week ending May 14) and all eight international forecast models used by the Bureau predicted that this warmth will be sustained through the middle of 2023.

Image: Sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific Ocean on May 20, 2023, showing abnormally warm water in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Source: NOAA

However, despite clear signs that the ocean was in an El Niño-like state, the atmosphere (trade winds and Southern Oscillation Index) was still stuck in a neutral pattern at the beginning of last week.

But late last week, one of the atmospheric indicators pushed past the El Niño threshold. The 30-day Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) – which measures the atmospheric pressure difference between Tahiti and Darwin – dropped below -7 on May 16 and has remained between -7.1 and -8.3 since then. This is the first time the 30-day SOI index has reached the El Niño threshold of -7 since the middle of 2020.

Image: Rolling 30-day SOI index between January 1, 2021 and May 20, 2023.

It’s important to point out that simply reaching -7 on the SOI index isn’t enough to declare El Niño. Due to the variable nature of the SOI signal, negative values of -7 or lower need to be sustained for around three months before the Bureau officially declares El Niño.

The recent dip in the SOI in the first main sign that the atmosphere may be starting to respond to the recent El Niño-like warming in the Pacific Ocean.

If El Niño does develop in 2023, it would increase the likelihood of above average daytime temperatures, overnight frosts and fire weather, and below average rain and snow in large areas of Australia during the second half of the year.

DTN APAC can provide tailored climate briefings, addressing climate drivers such as SAM, El Niño/La Niña and the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), to your business to alert you of the most likely weather conditions and hazards to look out for during the upcoming season. Now is a good time to get a good look at the forecast for winter, spring and beyond. To find out more or to book a presentation, please email apac.sales@dtn.com.