Despite the ocean giving clear signs that El Niño could form later this year, a lack of feedback from the atmosphere is giving forecasters a reason to be cautious in their outlook.

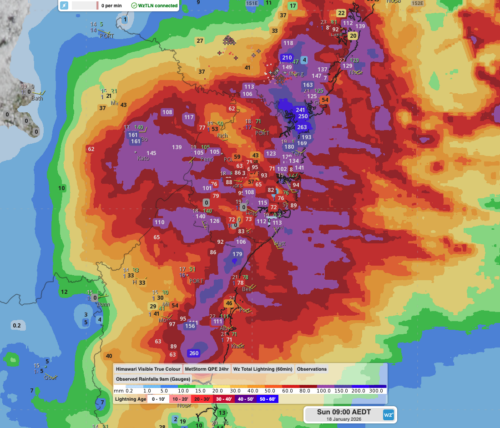

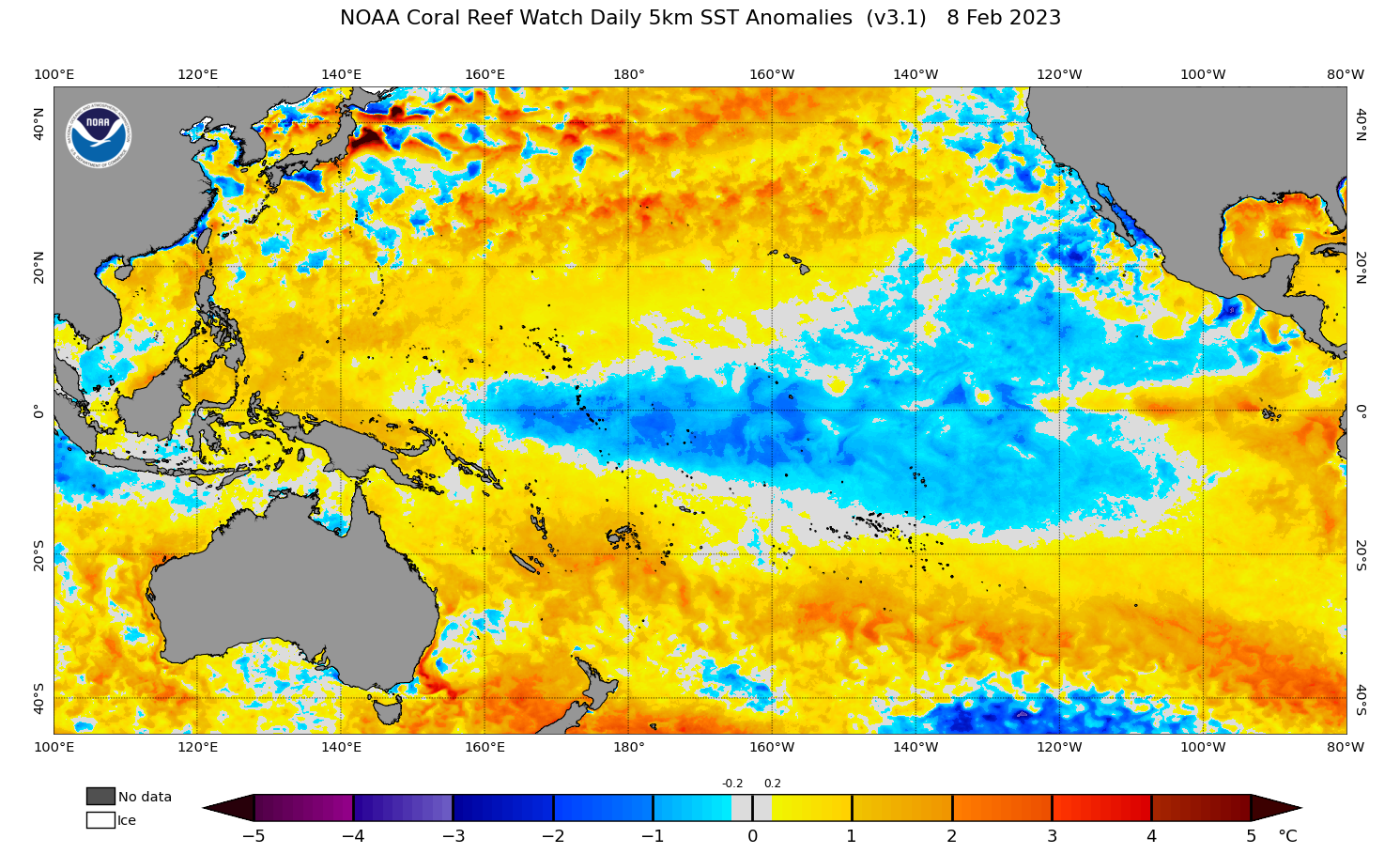

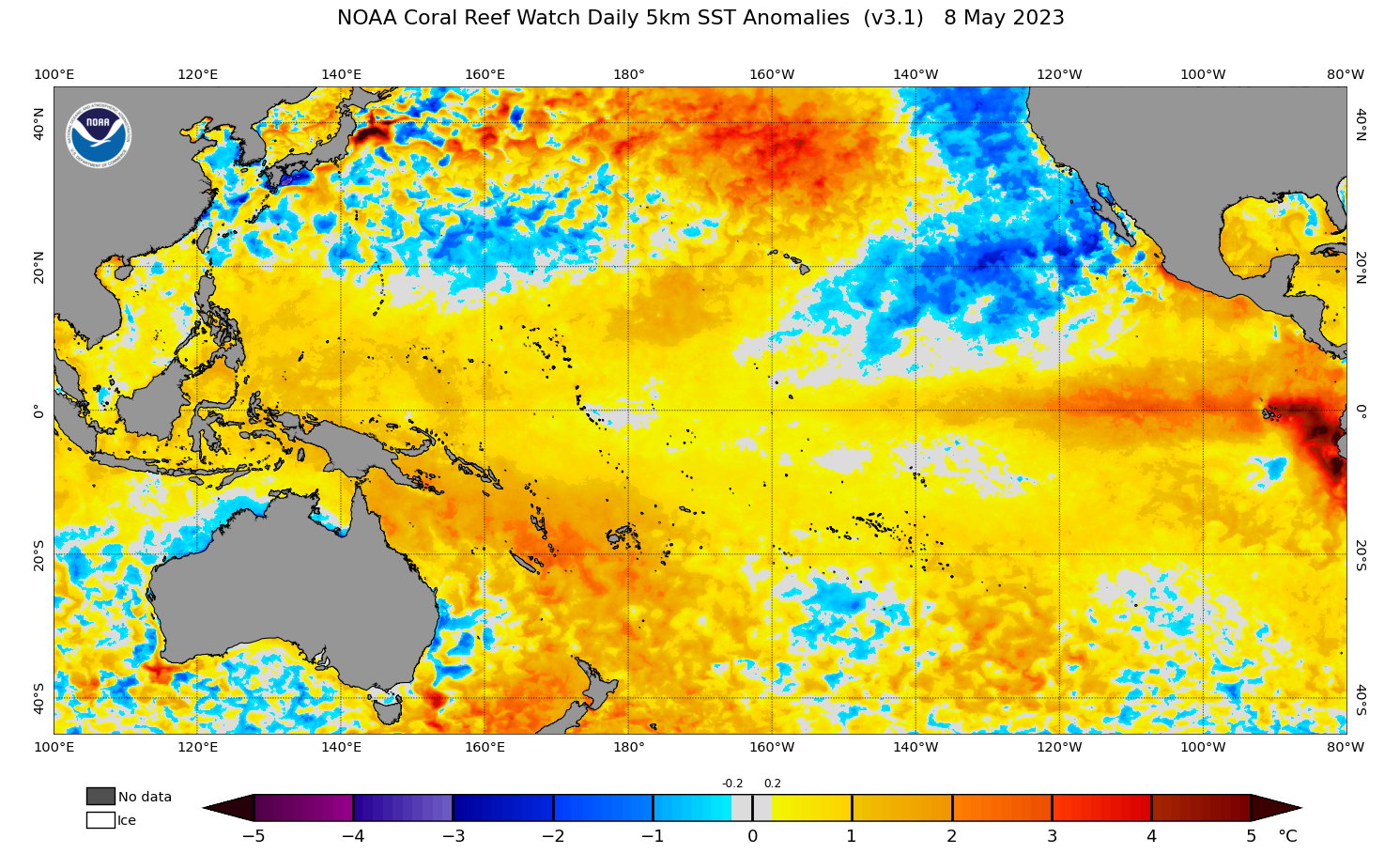

An abrupt period of warming across the equatorial Pacific Ocean has seen an El Niño-like pattern of sea-surface-temperature anomalies emerging in recent months. This transition can be seen clearly in the images below, which show cool surface water from the recent La Niña giving way to warmer water in the western Pacific over the last three months.

Images: Sea surface temperature anomalies across the Pacific Ocean on February 8 and May 8, 2023. Source: NOAA

All international forecast models predict that warming will continue in the equatorial Pacific during the coming months, likely reaching levels that exceed the oceanic threshold for El Niño during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter.

However, El Niño is a coupled ocean-and-atmosphere climate driver. This means the sky above the Pacific Ocean needs to respond to the ocean warming beneath it before a fully-fledged El Niño can be declared.

.png)

Image: Typical oceanic and atmospheric components of El Niño.

At this stage, the atmosphere is showing no signs of responding to the recent El Niño-like warming in the tropical Pacific Ocean.

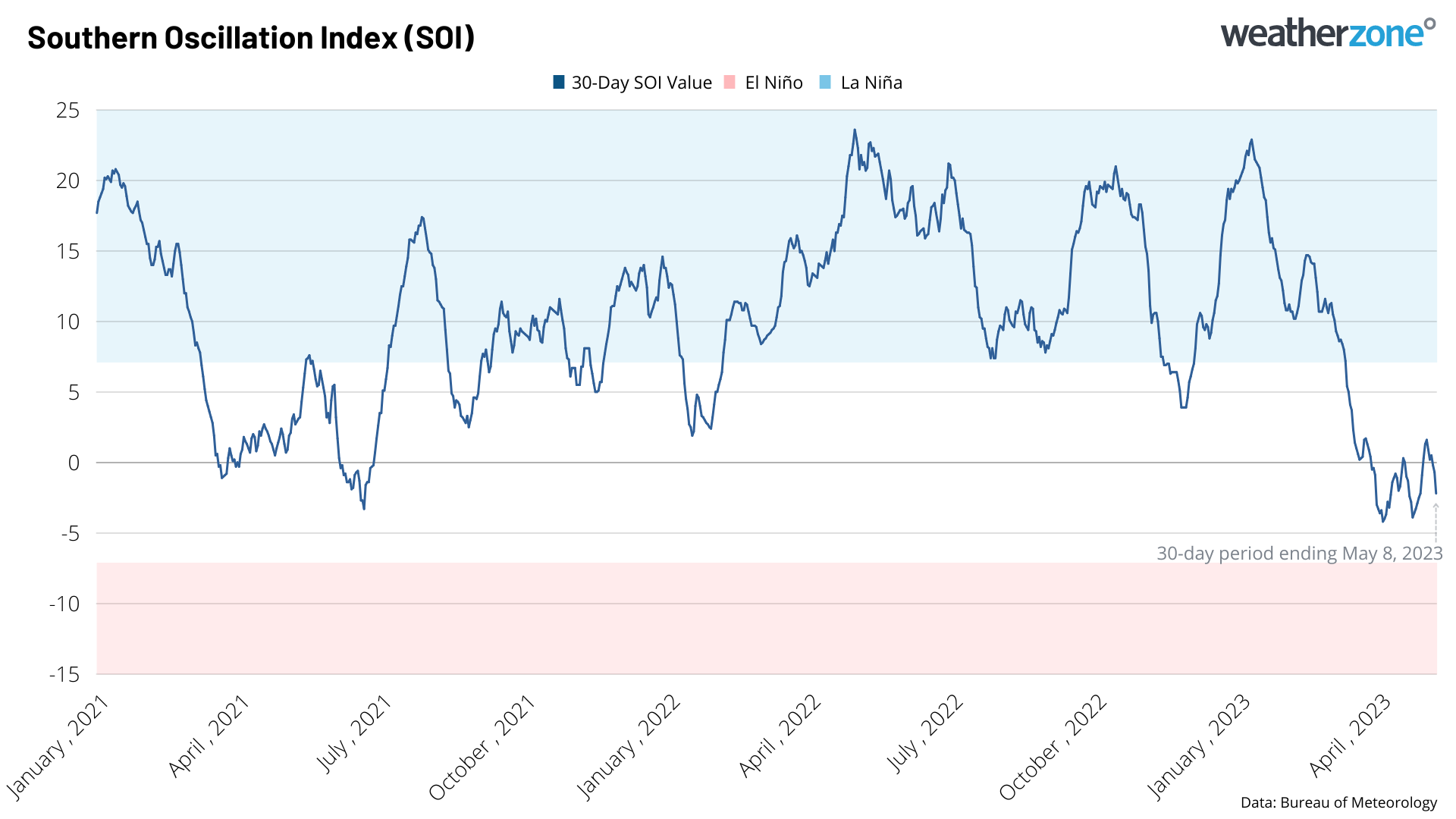

The Southern Oscialltion Index, which measures the atmospheric pressure difference between Tahiti and Darwin, needs to be consistently below -7 for El Niño. The latest 30-day SOI value was only -2.2, nowhere near the El Niño threshold.

Image: 30-day SOI index values between January 1, 2021 and May 8, 2023.

The easterly trade winds that flow across the equatorial Pacific Ocean were also near-average in the past week. During El Niño, these trade winds would weaken or even reverse in direction.

If the atmosphere continues to defy the ocean, the emerging El Niño could fizzle. But if the atmosphere becomes coupled with the ocean, there is potential for a strong El Niño later this year.

To make matters more troublesome for long-range forecasters, the atmospheric component of El Niño can only be reliably predicted about two weeks in advance. Until the atmosphere starts responding to the oceanic warming in the Pacific Ocean, forecasters can’t do much more than sit tight and see what happens.

Historically, forecast guidance usually starts to become more reliable as we move out of the Southern Hemisphere’s autumn and into winter, so a clearer picture should start to emerge in the coming weeks.

If El Niño does develop this year, it will increase the likelihood of below-average rain and above-average daytime temperatures over large areas of Australia. It would also raise the odds of a below-average snow season in the Australian alps.

DTN APAC can provide tailored climate briefings to your business to alert you of the most likely weather conditions and hazards to look out for during the upcoming season. Now is a good time to get a good look at the forecast for winter, spring and beyond. To find out more or to book a presentation, please email apac.sales@dtn.com.