Over the past few months, the stratosphere around Antarctica has been cooling, and that cooling is now starting to influence our weather in the lower atmosphere.

What is the stratosphere?

All the weather we experience on the surface of Earth occurs in the troposphere, which is the lowest 5 to 10km of the atmosphere.

The next layer of the atmosphere above the troposphere is called the stratosphere, which extends from a base of 10 to 20km elevation up to about 50 kilometres. It is home to the ozone layer that protects us from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation.

Image: Diagram over the Earths atmospheric layers. Source ECMWF

Unlike the troposphere, the stratosphere is very dry and has little influence on our day-to-day weather. However, conditions in the stratosphere can still influence the behaviour of weather system in the troposphere, especially near our planet’s poles.

One way the stratosphere interacts with the troposphere is through the influence of the polar vortex.

The polar vortex is simply a large band of powerful stratospheric winds that flows around our planet’s north and south poles in the cooler months of the year. The strength and shape of the polar vortex in the stratosphere can influence weather systems in the troposphere.

This year, the stratospheric polar vortex has been unusually strong and cold, which may lead to changes in the weather across the Southern Hemisphere over the coming months.

Why is the stratosphere cooling?

There is a bit of uncertainty as to what has caused cooling to occur in the stratosphere in recent months, but there is one very clear suspect: the volcanic eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai on 15th January this year.

The Tongan volcanic eruption was one of the largest explosions ever recorded by satellites and the strongest volcanic eruption since the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo. As it was an underwater volcano, it released an enormous amount of water vapour through the atmosphere, even reaching beyond the stratosphere and into the mesosphere, about 57km above Earth’s surface.

This single eruption increased the amount of water vapour in the stratosphere by about 10%, with the majority of that staying in the southern hemisphere.

This vast accumulation of water vapour reflects more of the suns light and energy back into space compared to ozone and other gases that make up the stratosphere. Over time, this has allowed the stratosphere to cool.

Image: The southern stratospheric cold anomalies (shown here at 50 hPa, or about 20 km) are gradually converging on the pole. Source NCEP-GDAS NOAA

What impact has there been so far this year?

The cooling of the stratosphere has meant that the polar vortex was very stable during autumn, winter and spring. When it is stable like this, there are fewer cold fronts that push up and affect Australia. This is represented by the positive Southern Annular Mode (SAM) that has been present virtually all year.

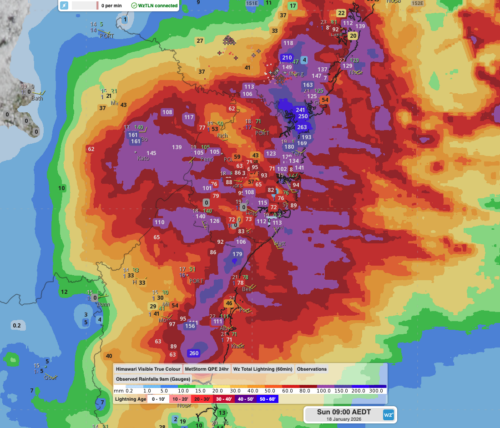

For eastern Australia, this increases easterly winds that, when paired up with La Niña, has led to one of the wettest years on record, especially in NSW and Victoria. For Western Australia and western Tasmania, this lack of fronts has led to drier than normal conditions.

Image: Effects of a positive SAM in winter (left) and summer (right) months

What is changing now and how will it affect Australia over summer?

The cool stratospheric air is now descending into the troposphere, the layer where we live, and where all our weather occurs. Cold fronts are becoming colder as a result, and more frequently bringing bursts of cold weather across the southeast (like the snow and chill we’ve seen over the last few days).

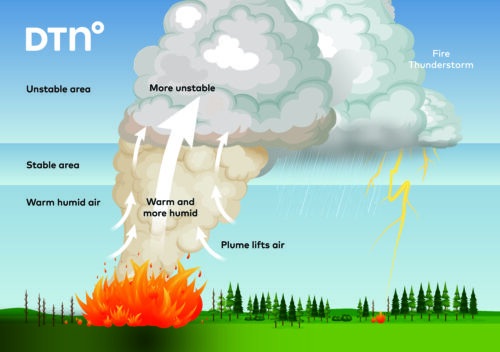

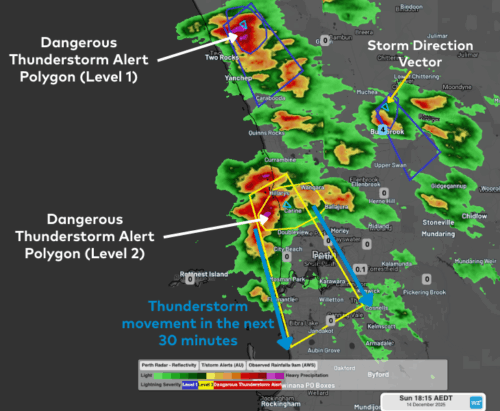

Another consequence of these stronger cold fronts is more severe thunderstorms. Stronger fronts during the spring and summer months increase instability and provide a trigger to create the storms. The only other necessary ingredient for storm formation is moisture, something that is clearly not lacking over central and eastern Australia at the moment.

While the cooling polar vortex will have an impact on our weather this summer, it is still being held back a bit by the positive SAM. This is expected to occur for as long as La Nina hangs around, as there is a strong correlation between the two climate drivers.

So, cold fronts will not necessarily be more frequent, but they are more likely to pack a stronger punch when they do occur. This means we could see more thunderstorm outbreaks similar to last weekend’s as well as more snow events.

To find out more about Weatherzone’s climate forecasts and briefings and how this event could impact you, please email us at apac.sales@dtn.com.