Australia could see a lacklustre snow season this year if an anticipated unfavourable combination of Pacific and Indian Ocean climate drivers comes to fruition.

The Australian snow season is notoriously fickle. Some years can see heaps of snow coming from multiple large snow-bearing systems (e.g. 1981, 1990, 2000), while other years barely have enough snow to cover the ground at some ski resorts (looking at you 2006).

So, what makes a good or bad year and what will the Australian snow season look like in 2023?

Image: Snowmaking at Falls Creek, Vic on May 18, 2023, laying the snow base for the season ahead. Source: Falls Creek

First up, it’s important to note that we can’t yet predict how many individual snow-bearing systems will hit southeastern Australia this season, or exactly how much snow will fall. These factors will come down to individual weather events that can only be predicted around 7 to 10 days in advance.

Fortunately, there is one thing we can look at now to predict what the upcoming snow season may have in store: the ocean temperatures around Australia.

Unlike the atmosphere, which changes a lot from week to week, the ocean takes a long time to warm up and cool down. This makes ocean temperatures more predictable weeks to months in advance.

Research carried out by Acacia Pepler, Blair Trewin and Catherine Ganter from the Bureau of Meteorology found that certain patterns of sea surface temperatures in the Indian and Pacific Oceans influence snowfall in Australia.

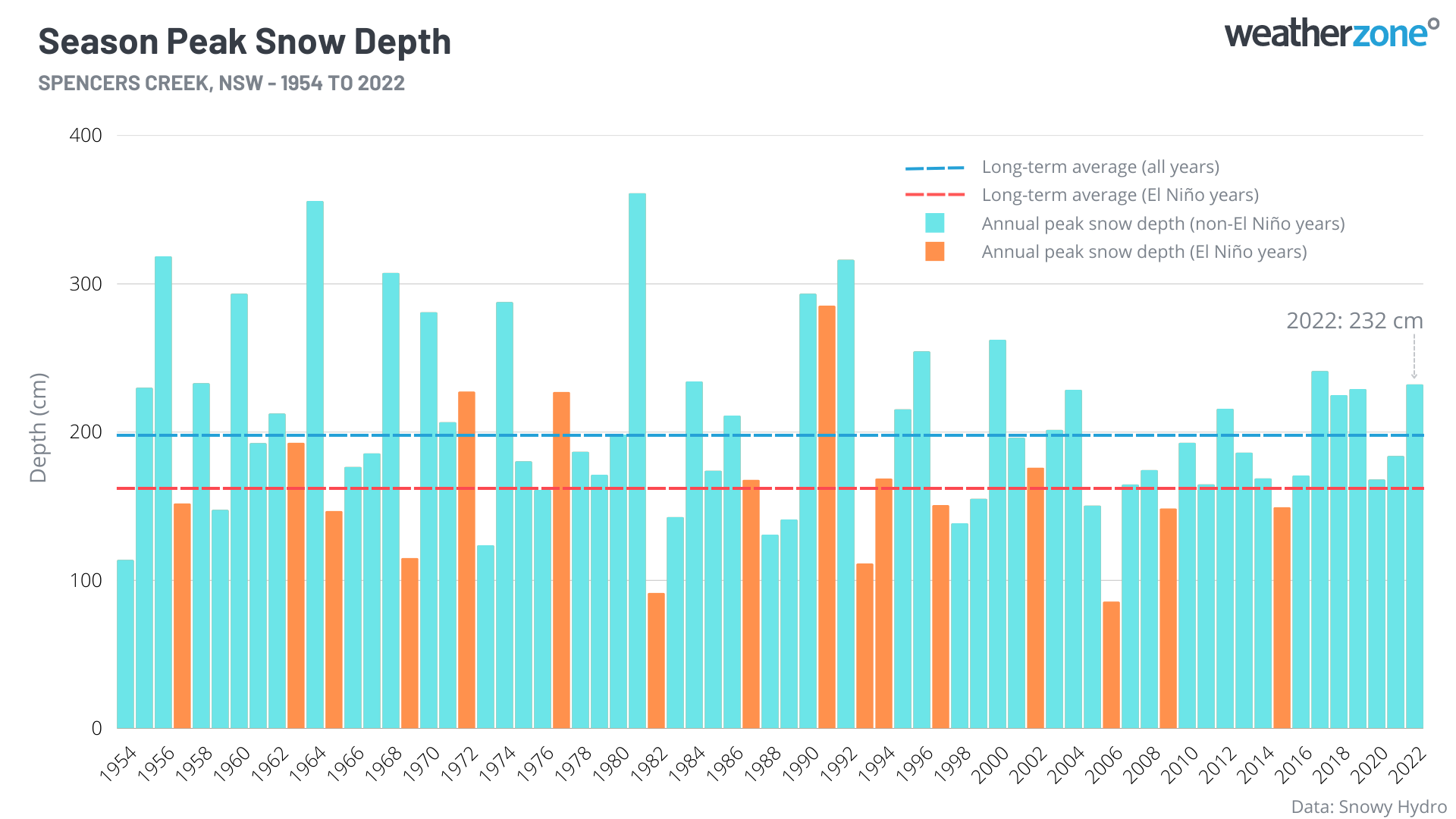

According to this study, the average seasonal maximum snow depth at Spencers Creek in NSW (elevation 1830m) is around 23 percent lower during El Niño years than it is when the Pacific Ocean is in a neutral state. The researchers also found that the snow-supressing effect of El Niño is present throughout the whole season.

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) – an index measuring the contrast in sea surface temperatures across the tropical Indian Ocean – can also influence Australia’s peak snow depth from season to season. On average, season peak snow depths at Spencers Creek are around 26 percent lower during positive IOD years compared to negative IOD years. This contrast is even greater later in the season (44 percent in early October).

The worst combination of Pacific and Indian Ocean climate drivers for Aussie peak snow depth is El Niño and positive IOD. While this combination has only happened eight times since 1960, it was responsible for the only two years that saw less than 100 cm of snow at Spencers Creek (1982 and 2006).

Based on snow measurements dating back to 1954, the average season peak snow depth at Spencers Creek is around 198 cm. This average drops by around 36 cm when El Niño is in place and slightly more when both El Niño and a positive IOD join forces.

Image: Season peak snow depths at Spencers Creek, highlighting El Niño years compared to all other years since 1954.

Unfortunately for Australian snow-lovers and industries that rely on the winter snowpack, both El Niño and a positive IOD are predicted to occur in 2023. If they do materialise, the Australian alps may have a poor snow season by historic standards.

However, it is important to reiterate that while El Niño and a positive IOD increase the likelihood of a below-average snow season, they don’t guarantee it.

Any season’s overall snow depth ultimately comes down to the frequency and strength of cold fronts, and the amount of time available for artificial snowmaking at the ski resorts. Even El Niño and positive IOD years can be saved by a few strong (or lots of weak) cold fronts, and the clearer skies produced by these two dry-phase climate drivers can provide better conditions for overnight snowmaking.

DTN APAC can provide tailored climate briefings to your business to alert you of the most likely weather conditions and hazards to look out for during the upcoming season. Now is a good time to get a full look at the forecast for winter, including the snow season. To find out more or to book a presentation, please email apac.sales@dtn.com.