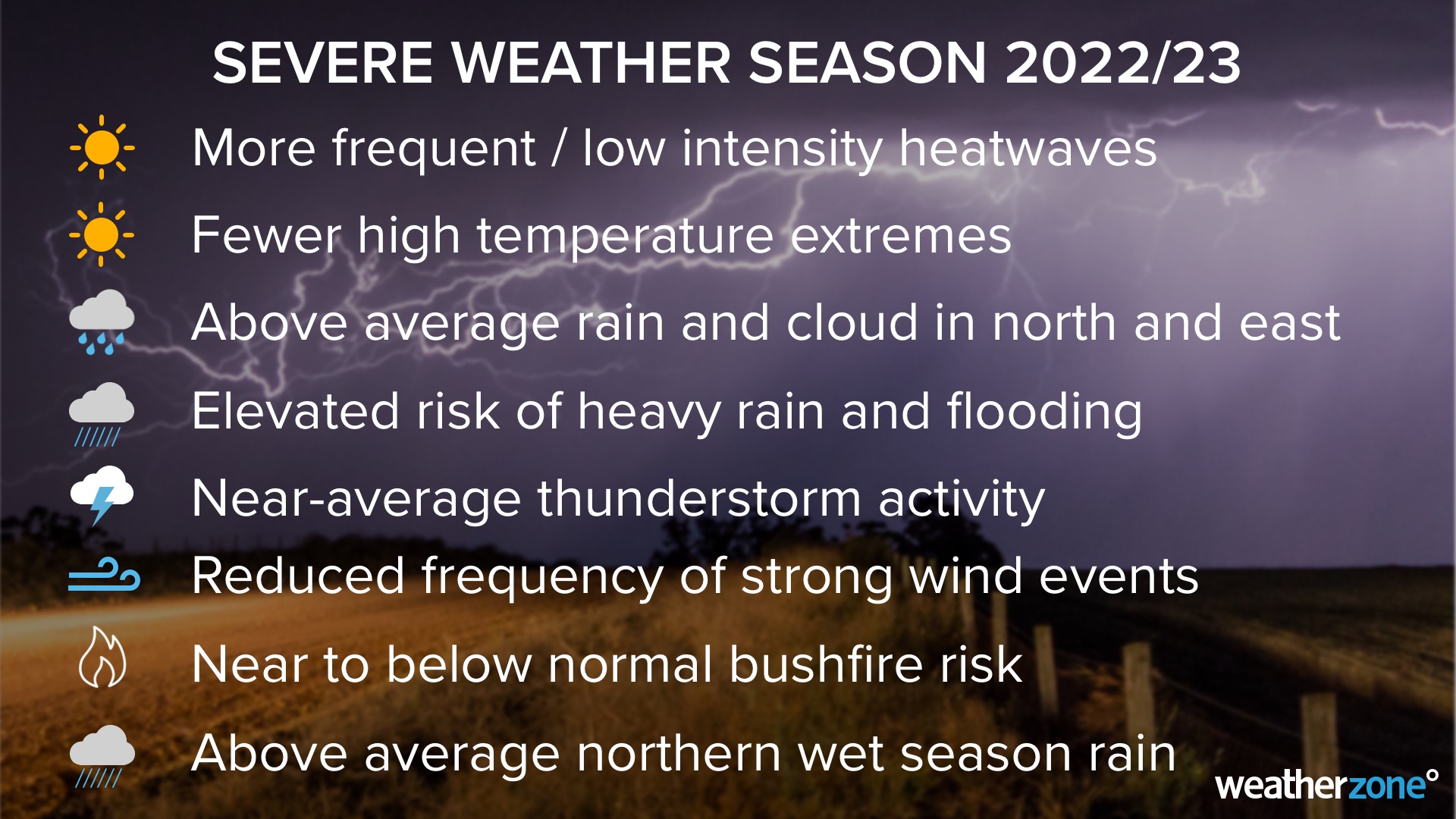

Australia’s severe weather season runs from October to April, during which time thunderstorms, bushfires, heatwaves, flooding and tropical cyclones become more likely. But not two severe weather seasons are the same, so what does this one have in store for Australia?

Australia’s climate drivers

Australia will enter the severe weather season under the influence of three wet-phase climate drivers:

- La Niña in the Pacific Ocean to the northeast of Australia

- A negative Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) to the northwest of Australia

- A positive Southern Annular Mode (SAM) to the south of Australia

All three of these climate drivers increase the likelihood of rainfall, cloud cover and flooding in Australia. You can read more about La Niña, the IOD and SAM here, here and here.

Seasonal forecast models suggest that La Niña should persist until the end of 2022 and reach a peak in strength around November, before weakening in December and most likely breaking down early next year.

The Indian Ocean Dipole should persist until the end of spring and most likely end at the beginning of summer. It is normal for IOD events to rapidly decay with the arrival of the monsoon in early summer.

The Southern Annular Mode (SAM) is also expected to remain in a predominantly positive phase during the rest of 2022.

Based on this outlook, Australia will most likely remain under the influence of these wet-phase climate drivers for the remainder of 2022, with La Niña and a positive SAM possibly lingering into the start of 2023 as well. This is likely to have a noticeable influence on Australia’s weather during the 2022/23 severe weather season.

Rainfall and thunderstorms

Rainfall

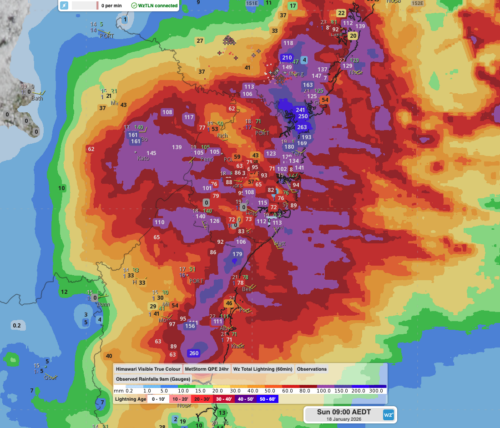

Above average rain is forecast across large parts of Australia during the remainder of spring and early summer. There will also be an increased chance of heavy rain events and flooding in the coming months, particularly over the eastern half of Australia.

The influence of three wet phase climate drivers combined with an already wet landscape from the past two La Nina years is expected to further exacerbate the impacts in Australia.

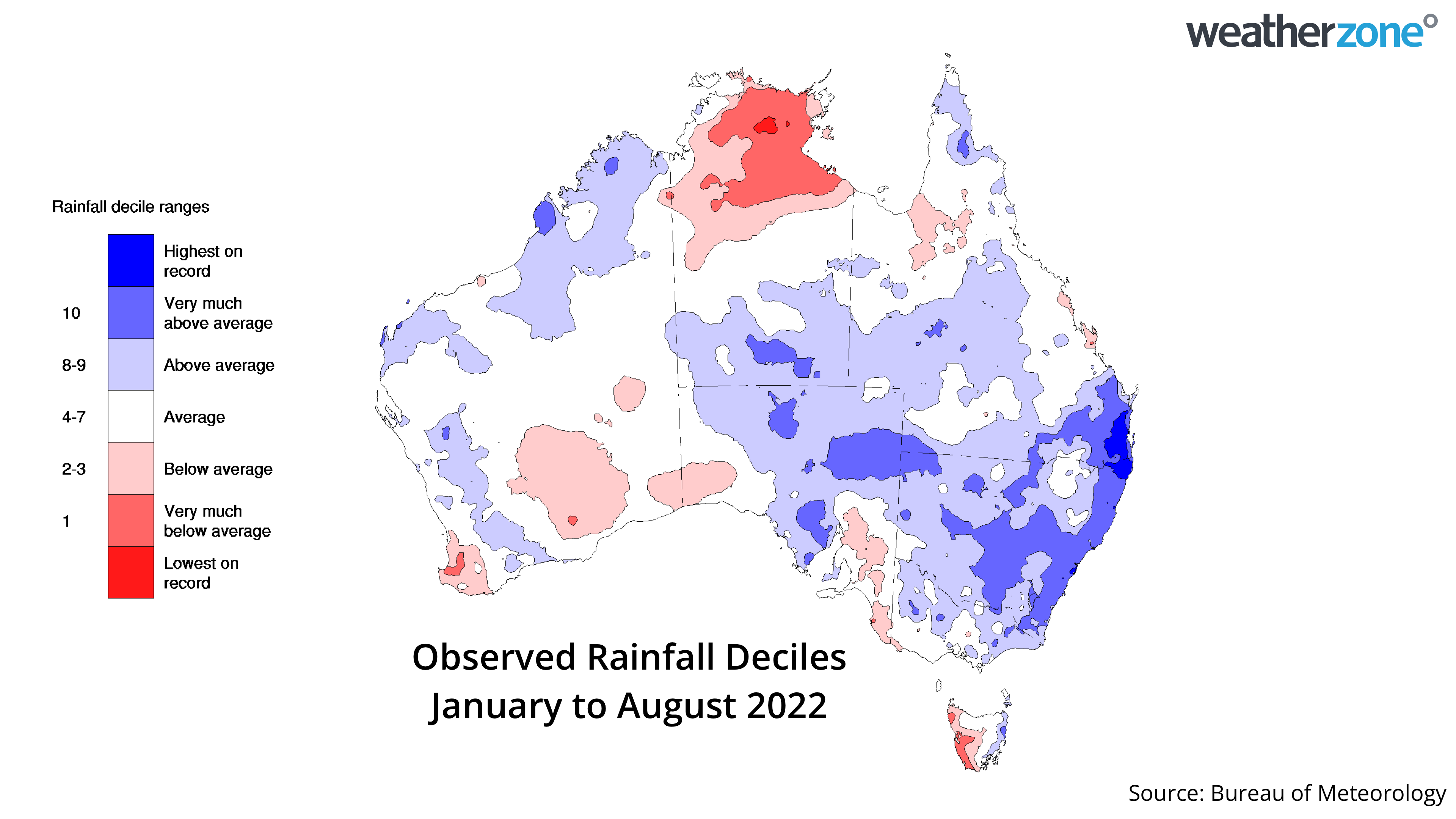

So, while individual La Niña events usually cause more rain and flooding in northern and eastern Australia, any La Niña-fuelled rainfall this year will be falling onto already saturated ground and into full dams. This makes flooding a heightened risk, especially for areas that have seen above-average rain in recent months.

Image: Observed rainfall deciles during the first eight months of 2022, showing that large areas central and eastern Australia have had a wetter-than-average year to date.

It is worth pointing out that no two La Niña events are the same and places that experienced flooding during last season’s La Niña are not guaranteed to see more flooding in the coming months.

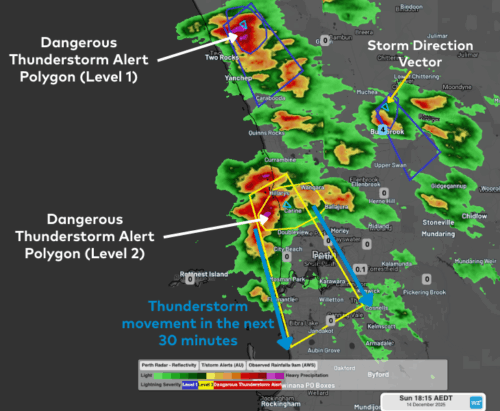

Thunderstorms

Thunderstorms happen over large areas of Australia every spring and summer and require three key ingredients to develop:

- Sufficient moisture in the lower levels of the atmosphere.

- Instability in the atmosphere.

- A trigger to initiate the storm.

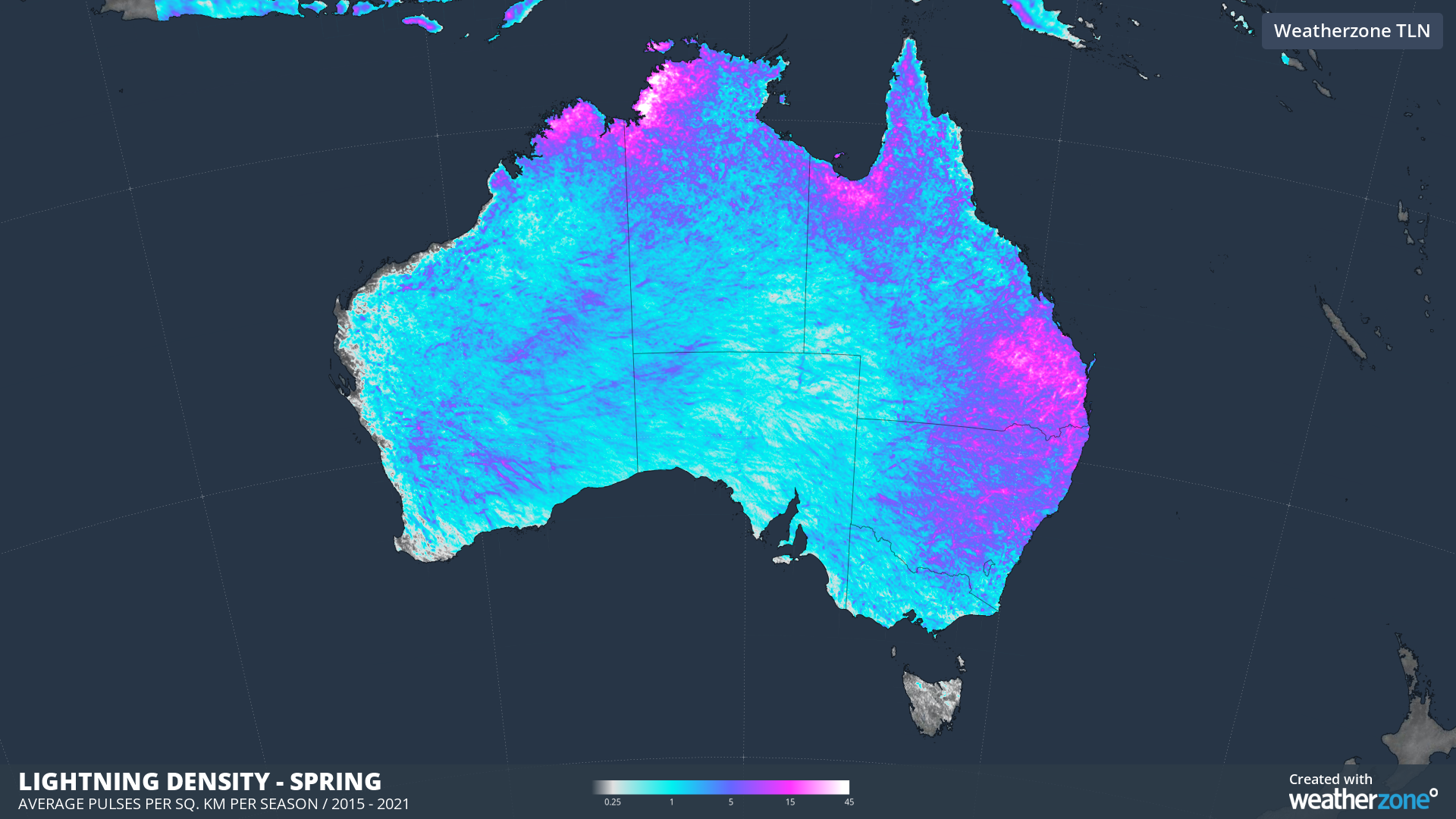

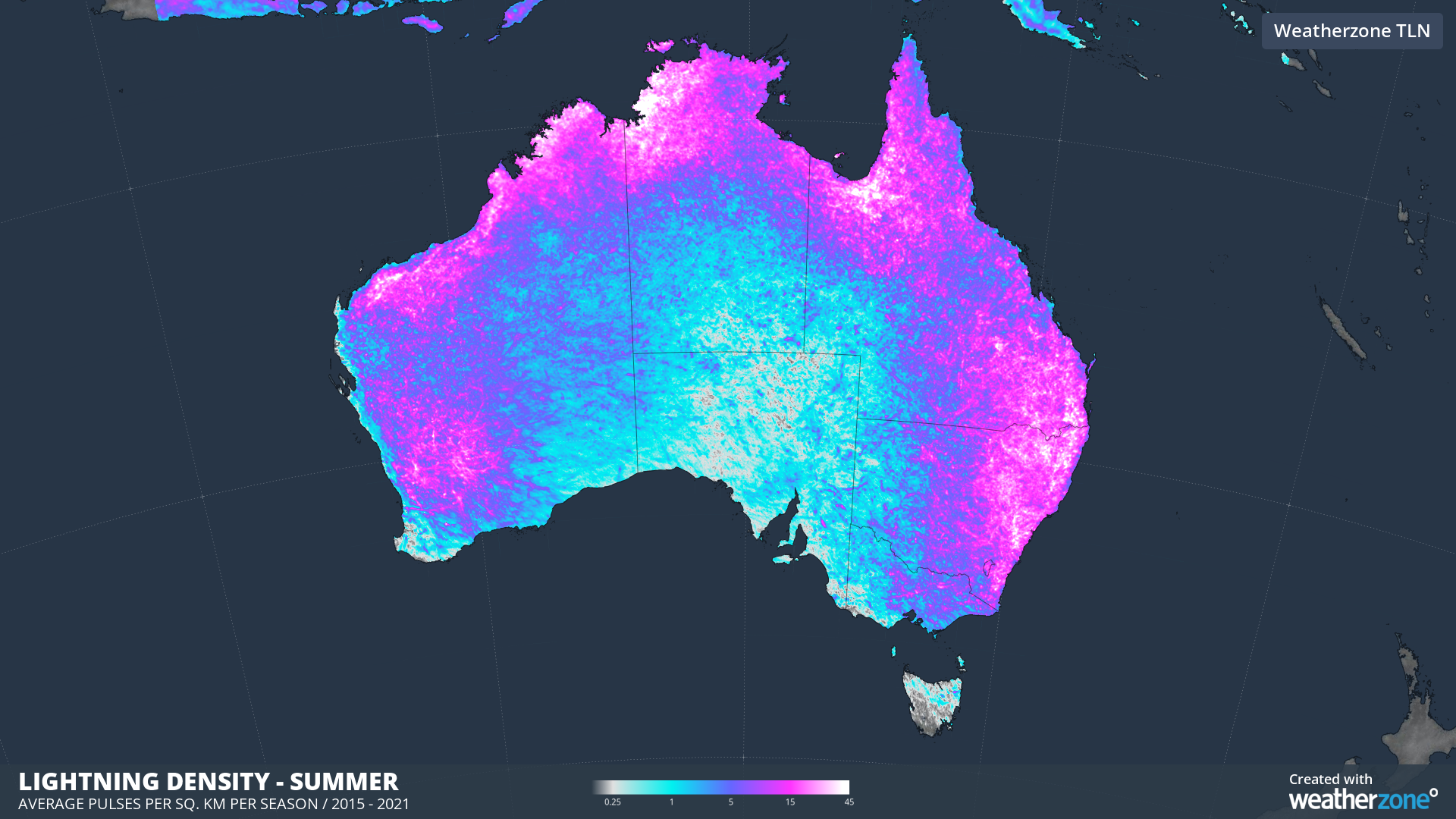

Images: Mean lightning density in spring (top) and summer (bottom) based on all lightning pulses detected by Total Lightning Network between 2015 and 2021.

During the rest of spring and the first half of summer, La Nina and positive phases of SAM should increase the amount of moisture available to fuel storms across eastern and northern Australia. Under La Niña, storm activity also shifts a bit further west, becoming less likely near the coast in eastern Australia and more likely over the country’s central and eastern Interior.

However, positive SAM and La Niña can also reduce the instability and triggers required for storm development, particularly in southern and eastern Australia.

As these influences counteract each other in the next few months, we expect to see near-normal thunderstorm activity in southern and eastern Australia, with a shift towards more inland storms over eastern Australia. Normal to above normal thunderstorm activity is anticipated across northern Australia.

Severe storms are still likely to produce large hail, damaging wind and heavy rain on a regular basis in the coming months.

If La Niña breaks down as expected early next year, storms will likely become more frequent and intense over Australia’s eastern states. This is because neutral ENSO conditions provide the most favourable setup for thunderstorm activity in Australia and there will be remanent moisture left near Australia.

Temperatures and heatwaves

The ongoing influence of this year’s negative IOD and La Niña will decrease the likelihood of extremely hot days during spring and early summer. However, heatwaves are more likely in southern Australia during La Niña seasons, but they are generally not as intense as El Niño years.

The number of days above 35 degrees are likely to be near or slightly below average for most capital cities in southern and eastern Australia. However, Perth is likely to see an above average number of days above 35 degrees, with more prevalent easterly winds dragging warm continental air over the city.

Tropical Cyclones

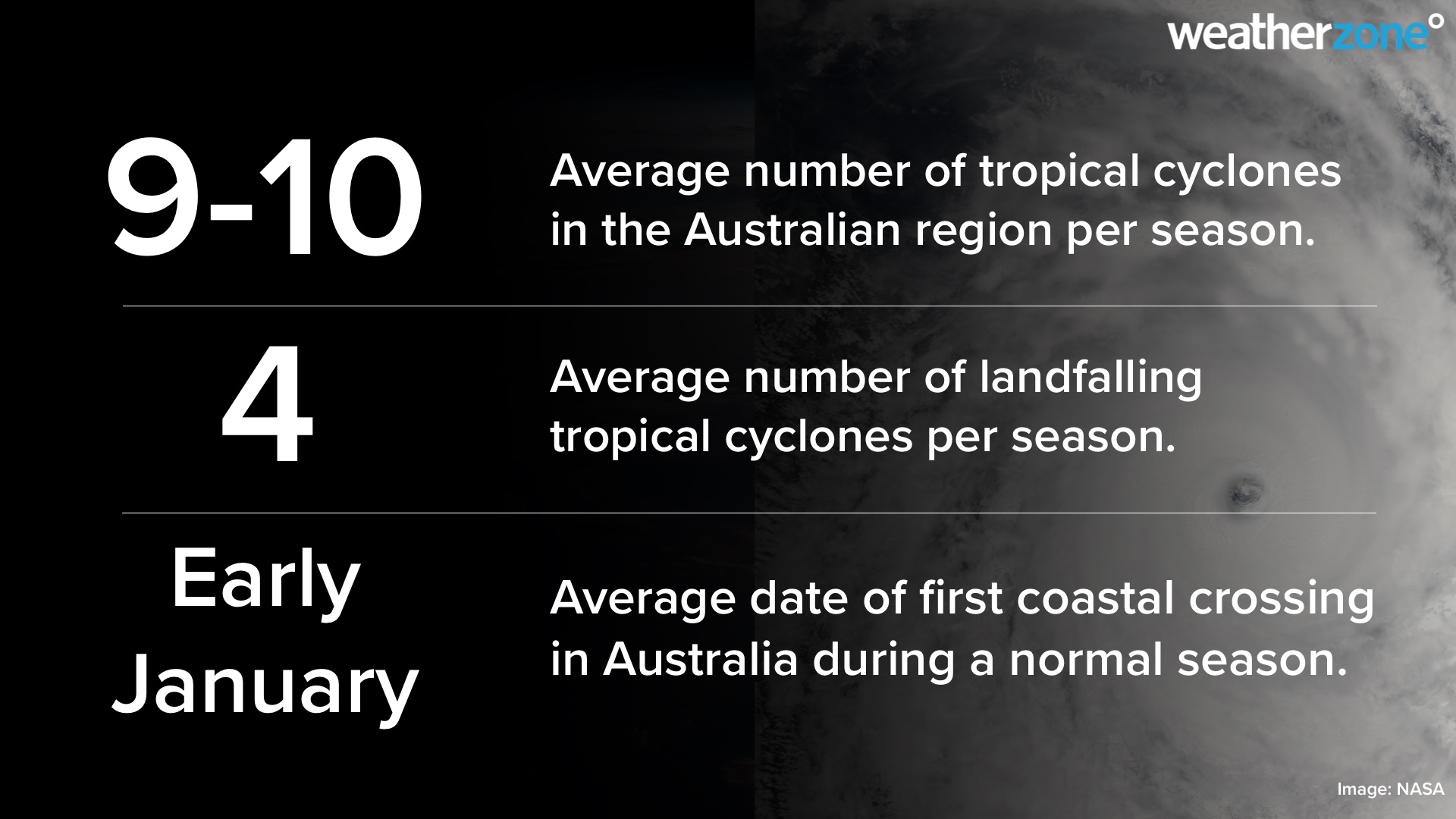

Australia’s tropical cyclone season runs from November until April and the first coastal crossing in Australia typically occurs in early January. On average, there are usually 9 to 10 tropical cyclones named in Australia’s area of responsibility each season.

The combination of La Niña and warm ocean temperatures near northern Australia should increase tropical cyclone and deep tropical low activity this season. Tropical Cyclone activity could also begin earlier this season thanks to the negative IOD and La Niña causing warm water to linger near northern Australia.

During La Niña years, the first tropical cyclone coastal crossing typically occurs around mid-to-late December, which is about half a month earlier than usual.

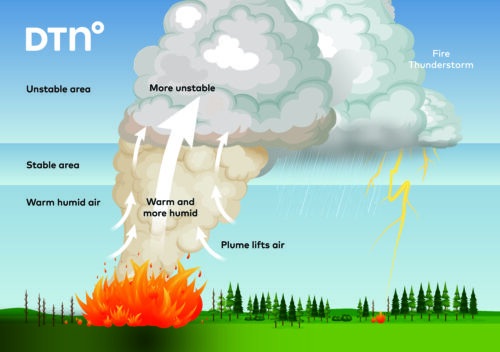

Bushfires

A confluence of wet-phase climate drivers will reduce the risk of bushfires across large areas of Australia in spring and early summer, although grassfires could still be prolific in some parts of the country.

Lower-than-normal fire potential is forecast across parts of eastern NSW, Victoria and the ACT in the next few months due to the combination of above-average soil moisture and rainfall. The recovering bushland from the 2018/19 and 2019/20 bushfire season could also suppress the potential for large and uncontrollable forest fires in the area during summer.

The risk of fires may increase in the second half of summer for some parts of Australia if La Niña breaks down as expected early next year.

Northern wet season

Northern Australia’s wet season runs from October to April. The first few months are referred to as the build-up, when moisture starts to build in the atmosphere, causing showers and thunderstorms become more frequent over the northern tropics. Rain then becomes more frequent and heavier with the arrival of the monsoon, which typically happens around late-December.

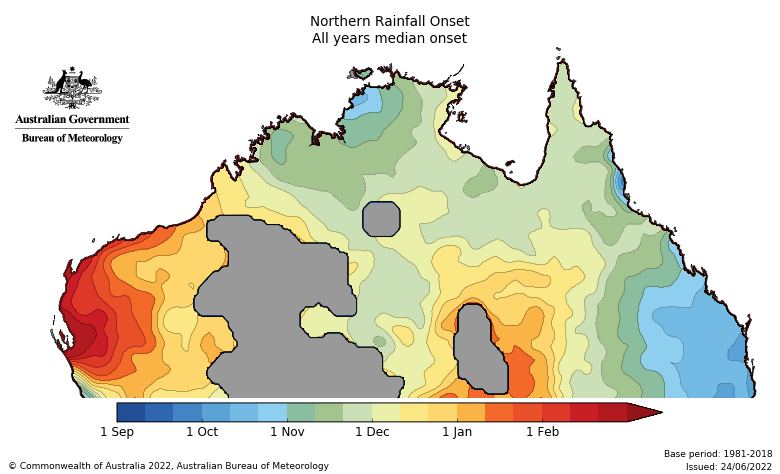

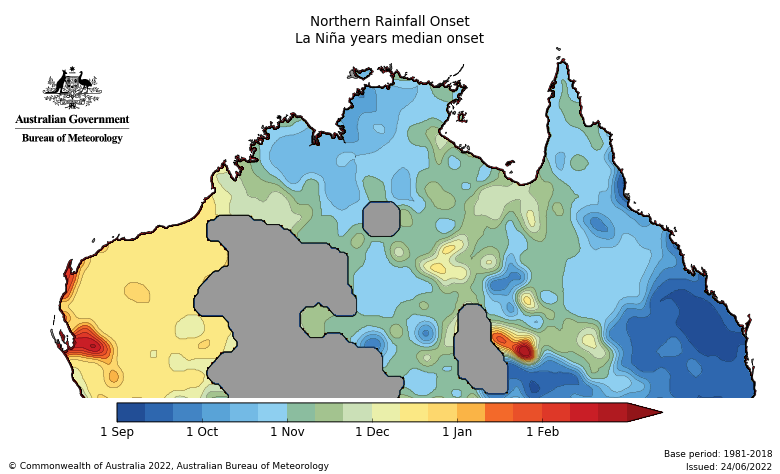

The first rainfall of the season that is sufficient to stimulate plant growth is referred to as the ‘northern rainfall onset’. This is defined as the date when 50 mm or more rainfall has accumulated after September 1.

In a normal year, the northern rainfall onset typically occurs in parts of coastal Qld and the NT’s Western Top End around late October or early November, before spreading to other areas of Australia’s tropics in the following weeks. However, during La Niña periods, the rainfall onset usually comes earlier, typically around early-to-mid October for large areas of the NT, QLD and far northern WA.

Images: Average northern rainfall onset dates in normal (top) and La Niña years (bottom). Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

The northern rainfall onset is expected to occur earlier than normal this season across Qld, most of the NT and possibly far northern WA. The rest of WA has roughly equal chances of an early or late onset.

A wetter-than-average wet season is predicted for QLD and the NT under the influence of La Niña. A near to below average wet season is expected over northern WA.

Wind

Strong wind events should be less frequent in southern Australia during early summer. This is due to the increased likelihood of positive SAM episodes during the remainder of this year and the associated suppression of cold fronts and low-pressure systems across the nation’s southern states.

While strong wind events are less frequent during La Niña and positive SAM, cold fronts and storms are still likely to move through and cause periods of increased wind this season.

During mid to late summer, increased frequency of strong wind events could occur when this La Nina event ends.

For more information about our seasonal forecasts, please contact us at apac.sales@dtn.com.